|

|

|

Introduction

Philips Lighting at Hamilton in Scotland was one of the principal global lamp factories for seventy years. Lampmaking was established in 1949 and it quickly grew to enormous proportions, peaking at 2300 staff. It was the only British factory that designed and manufactured not only the complete gamut of light sources, but also the control gear and luminaires to operate them as well as the machinery for their production. This resulted in the site building up a powerful competence in all aspects of the lighting industry. Following a major restructuring of Philips' global manufacturing footprint in favour of low labour cost countries, it began to decline in the late 1990s and one by one was stripped of its core operations. The low pressure sodium lamps section was spared and for many years Hamilton was crowned as the company's global competence centre for such lamps. However especially following the introduction of LED technologies for streetlighting, the sodium market began to decline and its gradual obsolescence led to closure in November 2019.

|

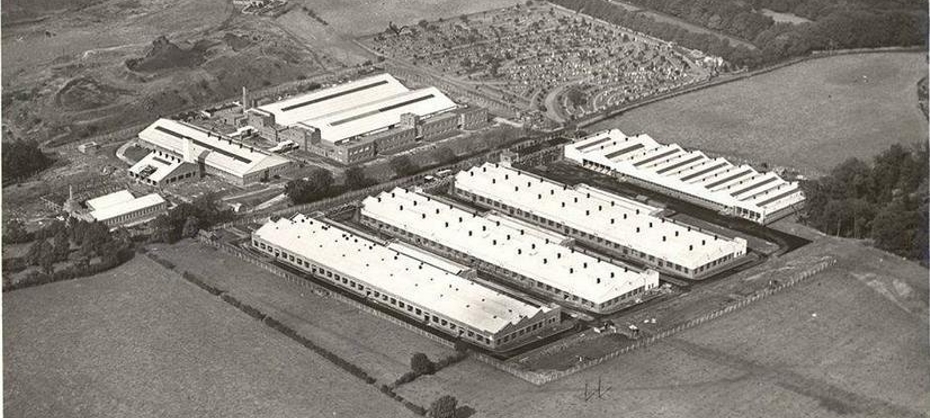

Aerial View of Philips Hamilton Site, 1958, prior to construction of the final two buildings

Aerial View of Philips Hamilton Site, 1958, prior to construction of the final two buildings

|

| Address |

Wellhall Road, Hamilton, Lanarkshire, ML3 9BZ, Scotland. |

| Location |

55.7711°N, -4.4671°E. |

| Opened |

1945, with start of lampmaking in 1949. |

| Closed |

2019 November. |

| Floorspace |

Unknown |

| Products |

GLS Lamps, Decorative incandescent, Reflector incandescent, Linear Fluorescent, Medium Pressure Mercury, High Pressure Mercury, Low Pressure Sodium, Miniature & Automotive, Photoflash, Ballasts & Control Gear, Commercial & Industrial Luminaires. Also radio sets, shavers, capacitors, and specialised military electronics. |

Start of Operations

During the Second World War the UK government ordered the major manufacturing companies to establish so-called 'shadow' factories in parts of the country far away from the major cities, so as to provide continuity of supply of critical war materials in case their principal factories should be bombed. Philips was one of the targetted companies, and was required to build a backup for its Mitcham works, an important producer of radio valves. A suitable site was identified at Hamilton in Scotland, and it was agreed that the building infrastructure would be constructed by the Scottish Industrial Estates Corporation, who would then lease this to Philips on favourable terms.

Construction began on 'A' Building in 1943, on the northwestern side of Wellhall Road in the Hillhouse district of Hamilton. The first buildings were ready in 1945 and in that year they were leased to Philips. Due to the end of the war there was no longer the same pressing need to establish a shadow valve factory, however Philips was still attracted to the region due to the copious supply of skilled labour at wage rates considerably lower than its factories in the south, along with attractive conditions for the lease of the site. This resulted in the assembly of radio sets at Hamilton in 1946, on such a great scale that this immediately occupied the whole site and within one year provided work to 1000 employees.

Expansion of the site was swift, with several more buildings being erected around the original works. By 1947 the entire land area had been occupied, and construction started on buildings H, J and K on the opposite southeastern side of Wellhall Road. However before they were completed, a trade recession dramatically reduced radio production.

A foundation stone for the new buildings was laid in 1947, which is sometimes erroneously cited as being the date when Philips Hamilton began operations. In fact that relates only to the second phase of the building works on the opposite side of the road. The two separate sites were later connected by a tunnel under the main road.

|

Start of Philips UK Lampmaking

Prior to the start of the Philips operations in Hamilton, the Dutch giant had a rather scattered lamps business in the UK. It had never built its own British factories and operated based on joint ventures and acquisitions of other smaller companies.

During the 1910s its leader, Anton Philips, was desperate to expand his manufacturing empire to the UK. Unfortunately for him, that country was substantially closed off to foreigners due to the immense power of the 'Lamp Ring', a cartel formed by the key British manufacturers. The combination of the cartel plus high import taxes created a powerful defence for many decades. The only realistic way for a foreigner to enter the British lamp market was to take over one of the members of the Lamp Ring, and thereby acquire the quota of how many lamps that company was permitted to manufacture each year. As attractive as the cartel might sound to the British lamp industry, it also ultimately led to their downfall because it encouraged acute stagnation of technology. The British lampmakers had little motivation to invest in improved lamps or more efficient manufacturing, so long as they were guaranteed continued business at extortionate selling prices. This situation began to change after WW1, when in particular the German Osram and Dutch Philips made enormous developments in manufacturing technologies which dramatically reduced lamp prices - so much so that even with hefty government import duties, they could gradually begin to sell on the UK market.

Foreign competition gradually threatened the established UK manufacturers, and Anton Philips' chance came in 1919 when he approached the ailing Ediswan company with a solution to its financial troubles. In exchange for 10% of the share capital he provided the company with state-of-the-art automatic lampmaking machinery built by Philips of Eindhoven, to allow it to return to profitability and increase its chances of survival.

The first manufacturing of Philips lamps in Britain was established in 1920 when a new building was created at Royal Ediswan's Ponders End works, to house the high-speed automatic Philips machines. However the installation, operation, management and quality of the lacklustre Ediswan team all fell below Philips' expectations. Friction between the companies was exacerbated when Ediswan fell into arrears in paying for the new equipment - but still paid out a hefty dividend to its shareholders. Philips had to initiate legal procedings to recover the debt, and this soured the relation to the extent that no further co-operation was possible between Philips and Ediswan.

Philips' next partner in the UK was with a small manufacturer that had been established prior to 1916 as the Harlesden Lamp Company Ltd., whose origins are not known. On the 21st April 1916 another business trading as the Stella Lamp Company was founded. It is not known if these two companies were related from the outset, but in 1921 an advertisement appeared featuring the joint names of the Harlesden Lamp Co. and Stella Lamp Co. both at the same Harlesden address. In 1924 Stella abandoned its own manufacturing in favour of sourcing from Tungstalite, and it is suspected that the Harlesden factory ceased operations at this time. However, in the same way as the UK Lamp Ring governed the quantity of lamps that could be sold at which prices, a similar situation was enforced worldwide by the 'Phoebus' International Lamp Cartel, founded and managed by the all-controlling GE of America. Phoebus provided security for its members, but strictly prevented any of them growing faster than others due to its quota system - instead all companies grew in parallel as the industry as a whole expanded. The only way for one member to grow its sales volume was by taking over a competitor.

In 1925-26 Stella was taken over by Philips so as to acquire its quota - which crucially included a small but significant share of the UK lamps market. It is not known if this also gave Philips a lamp factory in the UK, or if that had already been closed and Philips resurrected it later. Nevertheless it is certain that by the late 1930s, Philips was operating a British lamp factory at Harlesden, possibly on the same site as its predecessor. Philips maintained the Stella brand name for the the purpose of enlarging its sales channels. Previously Philips UK had exclusive agreements (in part enforced by the Phoebus cartel) that it would only sell its lamps at fixed prices via official distributors, who of course took a major share of the profit margins. Meanwhile cheap importers who operated outside the lamp ring were able to service a part of the market for which Philips lamps were too expensive. The Stella brand allowed Philips to sell a range of lamps direct to the wholesalers, no doubt with better margins for Philips but the final customers were able to buy Stella lamps at lower prices - by eliminating the monopoly of its former distributors. The different brand name was particularly beneficial as it avoided devaluing the existing Philips products. There was always a belief among customers that even though Stella lamps were made by Philips that they were somehow of lower quality, which may or may not have been true.

In parallel, Philips had associations with other British lampmakers. One of these was the Corona Lamp Works, which had been founded prior to the 1920s. In 1923 Corona and another British lampmaker, Cryselco, were attacked with litigation from GE of America's British subsidiary, BTH-Mazda, for infringement of its basic patents on gas-filled coiled-filament incandescent lamps. Corona and Cryselco took the unusual move of approaching their competitor Philips for help in defending them. This was a smart move which was actually in Philips' interests, because if BTH won its lawsuit, the British Gasfilled lamp market would most likely have fallen under the full monopoly of the British Lamp Ring cartel for the life of the patents. Corona also had its own manufacturing subsidiary for tungsten wire, the Duram Wire Company, which may have been of strategic interest to Philips. Philips therefore agreed to pay Corona and Cryselco's legal costs, and to support them with technical expertise from Eindhoven. The result was a successful ruling against GE and BTH-Mazda in the courts - but it appears that thereafter Corona was somehow transferred into Philips' hands. It is not known when the Corona factory was closed, but for many years afterwards Philips offered Corona brand lamps alongside its other cheap range of Stella lamps in Britain.

In 1927 Cryselco was taken over in equal share by both Philips and the lighting division of The General Electric Company of England, Osram-GEC. GEC took the lead in the day-to-day operations of that company's Kempston Lamp Works, with Philips providing the machinery and technical support. Cryselco continued operations as a 100% controlled lampmaker of Philips and GEC until the 1960s, when its production was abandoned in favour of sourcing from its parent company's much more efficient factories. Cryselco's luminaire manufacturing continued until much later. Philips also had a controlling interest in the Splendor Lamp Company of Holland, which operated a satellite factory in England. However, the UK Splendor operations maintained their independence from the Philips factories for much longer. That was because it was jointly owned together with other members of the Phoebus cartel, in which Splendor had special status as one of the so-called 'Hydra' factories whose purpose was to defend the Phoebus business from troublesome low-cost imports of non-cartel members in Japan.

|

Expansion of Hamilton

In 1949 Philips re-organised its manufacturing footprint in the UK, which resulted in part of the radio production moving from Hamilton back down to Croydon in the south. In parallel it was decided that Hamilton should become the country's principal operations for the Philips Lamps business. In that year the Harlesden factory was closed down, and all lampmaking was concentrated at Hamilton. Due to the greater degree of mechanisation in making lamps vs radios, the workforce fell to 700 at this time.

In 1950 the manufacture of Philishave shavers was established in Building H, a year later bringing the payroll to 1100 staff. In 1952 radio production returned from Croydon, along with another department for the manufacture of specialised military electronic equipment. The headcount saw an enormous boost in 1956 when it rose to 1500 to support the manufacturing of 'Photoflux' camera flashbulbs, these instantly expendable lamps being produced by the hundreds of millions. In 1957 the radio production was moved yet again back to Croydon, which pulled the workforce back down to 1200. However in 1961 it returned to 1800 when the manufacture of radio capacitors was relocated to the north.

By this time the manufacturing had reached vast proportions and it was clear that Philips would make a long-term commitment to its Scottish manufacturing base. The entire site was therefore purchased from Scottish Industrial Estates Corporation in 1961.

In 1964 work started on 'L' Building, a state of the art large new production hall at the highest point of the site. This was constructed according to a highly optimised design pioneered by Philips for its major lamp plants around the world, in which the manufacturing space was located on an upper storey with all gas, water and electrical facilities being delivered to the machines from a service space underneath. Of critical importance to a lamp factory, the floor was pierced at regular intervals by air vents which kept the production hall under slightly positive pressure, with a very slow and gradual uplift of air from the floor towards the roof vents. Such an arrangement naturally hinders the entry of dust via doors and windows, while substantially eliminating lateral draughts of air which can otherwise play havoc with the setting of gas fires on the glassworking machines. Two years later this advanced new building was ready, and in 1966 all gas discharge lampmaking was transferred from across the road into 'L' Building.

Also in 1966 work started on 'M' Building, the objective being to absorb all incandescent lampmaking from the scattered original buildings into one large new production space. The GLS manufacturing made this transition in 1967. By 1968 still more space was required for lampmaking, resulting in capacitor production moving down south to the Philips-Mullard factories at Blackburn. In that year a new chemical laboratory was opened. In 1974 the headcount stood at 1700, and this took a small setback in 1976/77 when it was decided to terminate manufacture of mercury lamps at Hamilton and many other Philips sites around the world, to focus on a single European mercury centre of excellence at Eindhoven in The Netherlands. In 1981 the manufacture of luminaires and ballasts was moved from Philips at Hull into 'J' Building, and that marked the final major expansion of Hamilton.

Gradually all of the operations migrated into the newer buildings on the southeastern side of Wellhall Road, and during the late 1980s the original buildings were demolished to make way for a supermarket and housing estate.

|

The SOX Lamps

Along with the Benelux countries, the UK has always been one of the principal consumers of Low Pressure Sodium lamps for outdoor and streetlighting. This is something Philips recognised in the 1940s. Despite having been first to commercialise the LPS lamp, Philips struggeled to break into the UK market due to the powerful monopoly and cartel situations along with a general preference for buying locally-made products. It therefore established sodium lamp production in Britain from an early stage, presumably at the Harlesden Lamp or Blackburn Valve factories. This was moved to Hamilton along with the rest of the company's UK lampmaking in 1949.

From that time onwards Philips operated two global sites for the production of sodium lamps : one in Hamilton and, the other at Eindhoven in The Netherlands. Other discharge lamps were still being produced by Philips all around the world, but during the period 1979-1986 Philips transferred the Eindhoven discharge production as well as much of its global competence in discharge lamps to the Turnhout factory in Belgium. However the low pressure sodium business was of such importance in the UK that Hamilton retained its SOX lamp production.

In the early 1990s Turnhout underwent enormous expansion, and required more floorspace to accommodate the booming volumes in metal halide lamp production, especially following its 1994 invention of the CDM Ceramic Discharge Metal-halide lamps. Space had to be freed up, and it was decided that Hamilton should become the global manufacturing competence centre for SOX lamps. As a result the second SOX line arrived in Hamilton in 1995. Manufacturing efficiency significantly benefitted from this combination. Rather than each site having to frequently change over each of their production lines from making low wattage small-diameter discharge tubes and outer jackets to the larger diameter high watts lamps, the original Hamilton line was dedicated to produce the low watts lamps while the ex-Turnhout line could be maintained for the production of the high watts.

The SOX department saw a major expansion in 2000 when Osram decided to abandon its own manufacture of these lamps, following the closure of its factory at Shaw. Simply sourcing the standard Philips lamp was undesirable for both parties. On the one hand, Osram had spent the past three decades advocating the superiority of its own dimple-free lamp construction, and it would have become instantly obvious to customers that it was simply sourcing a rebranded Philips lamp if the visual appearance had changed. On the other hand, Philips' own marketing story was that its dimpled lamps were superior, and did not wish to risk losing its market share by producing its own design for Osram. It was therefore decided that Philips should produce dimple-free lamps for Osram. Simply omitting the dimples from the Philips lamps would have led to reduced quality and problems of sodium migration, since the indium oxide heat reflector on Philips lamps has a near-constant film thickness. With the absence of dimples, that would cause sodium to be distilled from the hot electrodes end of the discharge tube to the colder U-bend, resulting in short life. Osram had countered that drawback by producing its lamps with outer jackets having a graded film thickness along the length, but this could not easily be produced with the Philips process. Therefore the only equipment actually moved from Shaw to Hamilton was the old Osram-GEC filming line, capable of achieving the graded coating thickness. Dimples were however added to some of the SOX-E ratings, just as Osram had also done on its own lamps.

Eventually the Osram filming equipment was discarded, following intensive efforts which allowed partially-graded coatings to be produced on the Philips machinery. This was no simple challenge, in view of the fact that the Philips machine could only coat ten-foot lengths of glass tubing, which were subsequently cut down to the shorter lengths for individual lamps. The Osram machine meanwhile coated one lamp envelope at a time, thereby facilitating the production of a graded film thickness along the tube length. The incentive for this change was an enormous cost saving, due to the fact that the Philips machine consumed about seven times less indium metal per lamp than the inefficient old Osram process. Indium is a particularly rare metal with extremely high cost, and it is therefore essential to minimise its wastage during production.

Hamilton realised another small increase in volume when GE Lighting abandoned its own SOX production in 2007 with the closure of its Leicester factory. Its volume was absorbed into increased sales of Philips and Osram lamps, since GE completely exited the business and did not source from other suppliers. The SOX production for Osram continued until around 2016 when that company finally exited the business, leaving Philips as the sole producer of global significance. A couple of small Chinese companies have attempted to produce SOX lamps, but so far none have achieved notable success.

|

Decline and Closure

The first substantial blow to Hamilton came as a result of Philips Lighting's Centurion Project of the 1990s, when the management became increasingly obsessed with decreasing its global manufacturing costs. From this period onwards there were tremendous plans to totally restructure its manufacturing footprint by moving as many operations as possible to low labour-cost countries. The lighting production was gradually relocated to one vast new low-cost hub for European markets in Poland, and another for the Americas in Mexico. Gradually there was additional emphasis on moving further afield to China, and eventually to abandoning manufacturing altogether in favour of sourcing lamps from even cheaper third party vendors.

For Hamilton, the first victim in this transition was the closure of incandescent manufacturing in 1997, when 'M' Building was vacated and all production moved to Pila and Pabjanice in Poland. Between 2004 and 2009 'M' Building was demolished, and around half the land area was sold off to make way for a housing estate.

Next the fluorescent manufacturing began to be wound down, decreasing from two lines producing five different lengths to just a single line for the 8-foot T12 lamps which were rather unique to the UK market. Even this came to a close in the early 2000s, when Philips quit that production in favour of sourcing from GE and Sylvania.

Towards the end of the 2000s the manufacture of control gear was moved out of 'J' Building to Ketzryn in Poland, and that entire division of Philips was subsequently sold off to the independent supplier Magnetic Systems Technology (MST). In 2013 Luminaires were the next point of attack, following Philips' ambitions to transition to full LED luminaires for outdoor and street lighting. This led to the entire range of streetlighting fixtures for SOX lamps being abandoned, with the loss of 133 jobs and bringing the workforce down to just 104. Shortly thereafter the redundant H, J and K Buildings were leased to third party tenants.

The only department which was substantially unaffected by this reorganisation was the SOX lamp production. The manufacturing of this lamp is far from easy and requires a particularly broad experience in countless different and often completely unique aspects of lamp engineering and production technologies. Perhaps because of the declining nature of this business, it did not make sense to relocate production to a new site. That would have required expensive long-term investments in training, and risk more quality disasters of the kind that had plagued the relocation of many other Philips lamp types.

A long-term plan was therefore made to extrapolate for how long the business could be maintained, which towards its end was severely influenced by significant rises in the cost of the raw materials. Especially after Philips decided to exit another core business of glass manufacturing, its Winschoten Quartz & Special Glasses plant in Holland was sold to QSil of Germany. As the SOX business began to decline, the cost of the special 2-ply borate glass tubing had soon doubled. This and other effects saw the price of SOX lamps begin to increase very sharply, which further accelerated the rate at which customers moved to high pressure discharge and LED alternatives for street and outdoor lighting. In the Autumn of 2015 another 30 jobs were lost as the plant was cut back to the bare minimum. Ultimately the unavoidable announcement of a planned closure was made in 2018, with customers having a final opportunity to place orders until July 2019. It was initially expected that this would keep the production running until the middle of 2020 - however the uptake was far less than expected and the date of closure was brought forward to the end of 2019.

The company had meanwhile been re-named "Signify" following the decision of the Philips board to completely abandon its increasingly weakened lighting business. As was becoming typical for Philips, its corporate management had proven itself unable to keep up with market transformations, despite having invested tremendously in remaining a technology leader. For instance when the global television industry transitioned from cathode ray tube to LCD panel technologies, the formerly giant Philips changed from being a global leader in technology, performance and profitability, to a monstrously loss-making corporation. Similarly as the lighting industry switched from conventional to LED-based technologies, Philips struggled to maintain its profitability despite having always been one of the most powerful driving forces in both the technological developments as well as the necessary market transformations.

In July 2019 it was announced that the Signify Hamilton factory would close in November of that year. During its final months the SOX lamp production was driven at full speed, so as to build up sufficient stock to fill the sales channels until the projected date at which this light source would be made obsolete. Production finally came to a close on 7th November 2019, with the loss of the final 70 jobs. This brought 70 years of lampmaking at Hamilton to its conclusion, and with it the end of low pressure sodium lighting technology. Far from being a slow and gradual death in the final months, it is a great tribute to the dedication of the employees that their production output and quality standards were maintained at their best ever, right up to the final date of closure.

|

Photographs

|

Foundation Stone, laid in 1947 Foundation Stone, laid in 1947 |

|

Buildings A through K, 1958 Buildings A through K, 1958 |

|

Building A, 1950s Building A, 1950s |

|

Buildings G,H,J,K,L,M, 1980s Buildings G,H,J,K,L,M, 1980s |

|

Building J, 2014 Building J, 2014 |

|

Buildings J,K,L, 2019 Buildings J,K,L, 2019 |

|

Building L, 2019 Building L, 2019 |

|

Apprentice Training Department Apprentice Training Department |

|

Building L Production, 1986 Building L Production, 1986 |

|

Fluorescent 8ft Horizontal, 1986 Fluorescent 8ft Horizontal, 1986 |

|

SOX Outer Bulb Forming, 1986 SOX Outer Bulb Forming, 1986 |

|

SOX Final Inspection, 1986 SOX Final Inspection, 1986 |

|

GLS Sealex Machine, 1986 GLS Sealex Machine, 1986 |

|

GLS Sealex Machine, 1986 GLS Sealex Machine, 1986 |

|

GLS Quality Department, 1986 GLS Quality Department, 1986 |

|

|

Examples of Hamilton Lamps

Fluorescent

High Pressure Mercury

Low Pressure Sodium

| 1 |

A Brief History of Philips Lighting Hamilton, 1974. Internal document from Frank Love & Charles Ramsay, GLS Department. |

| 2 |

Philips Hamilton - Lightmakers to the World. Internal Brochure, 1986. |

| 3 |

Report on the Supply of Electric Lamps, The Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Commission, HM Government, 1951. |

| 4 |

Second Report on the Supply of Electric Lamps, The Monopolies Commission, HM Government, 1968. |

| 5 |

Philips to shed 130 jobs at Hamilton factory, BBC News, 28th August 2013. |

| 6 |

Historic Hamilton - The Philips Factory, Garry L. McCallum, November 2019. |

| 7 |

Hamilton's Philips factory jobs blow - another 30 staff to go at iconic factory, Alastair McNeill, The Daily Record, 29th May 2015. |

| 8 |

End of an era as remaining 70 jobs at former Philips factory are to be axed, Hamilton Advertiser, The Daily Record, 11th July 2019. |

| 9 |

Private Communication, David Exon, Philips Lighting Croydon, 1995. |

| 10 |

Private Communication, Tom Ramsay & Derek Paterson, Philips Lighting Hamilton, 1996. |

| 11 |

Private Communication, Allan Court, Philips Lighting Hamilton, 2019. |

|

|

|

|

|